I remember being excited, as a philosophy student and aspiring writer, about Gilles Deleuze’s reminder that the philosopher is someone who invents concepts.

What power, I thought, to make things with your brain.

Youth often loves without substance and forgets that these inventions are real cuts into reality. They extend it. Later, experience tells us that concepts shift us towards a new perspective that we have to build ourselves. Words are never enough, you need a community of energised people understanding and building that new extended fabric of life with the philosopher, hinging on a deep relation with the new word’s exciting idea.

De-territorialisation was one such word, quite genius as far as new concepts go, because it did what it said on the tin: uprooting from a social or geographic territory by altering or destroying its structural elements. I remember reading later that this concept twinned with another one, re-territorialisation, which means reorganising the territory with the new structure. Both were brained by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. Understandable, iridescent, communicative in different ways to different people.

The subconscious, another one. Perfect. De-construction. Bang!(Jacques Derrida.)

Of course, not all concepts are immediately seductive and understandable. Anthropocene, a few years back, needed an explanation but once everyone was on board, it was a free-for-all. Anthropocene, the geological time when human impact on the planet superseded any other. The term may have been mysterious at first glance, but insofar as we’d had a good explanation for it, it had the magical effect of precluding us from any other contextualisation. It was used and abused in quite a few exhibitions, standing in, or rather standing over, a myriad of relations to the planet and its crisis that would remain unexplained. Nevertheless, I remember learning about it, and rejoicing in the existence of a scientific label to situate an atrocity.

Yes, us intellectuals, we love words, thoughts, ideas, complex meanderings we find obvious until someone unnervingly tells us they’re not. It would be ok to blame us, but I think it’s a collective phenomenon that involves time and scale. Once the precious word has gone around, explained, then used, then re-explained to those who live under a rock, then re-used, then mocked by a few or simply challenged, it has been worn out like a transitional blanket. It stinks, and it has lost its shape. No one remembers where it was picked up in the first place. It needs to be replaced by a new one.

There’s a positive spin to this verbophagia, which is that it operates like a symptom. You can trace the currents and undercurrents of a certain culture, the one where museums overlap with design, the education sector, left or centre politics, counter-culture (in the past), viral culture (currently), and to what extent the Big Money that supports Big Art is flexible in its mostly right wing politics: Palestine not so much, climate change yes, climate fight not so much, past feminisms yes, intersectional feminism not so much, crushed identities yes, self-affirming excluded communities depends, trans rights depends. The verbiage around art is the meteorology of our (good?) intentions.

But as far as things go, when you actually set foot in a museum, there is so much stuff, the work is so THERE, in its irreducible material form, or as an ambivalent surface, screen or mirror, that it seems protected by its own weirdness. Perhaps naively, I find that living at a time where schools can go to a museum or a gallery and read “QUEER BRITISH ART 1861 –1967” (Tate), is marvellous. Call me simple minded, but words are important.

What puzzles me is that the necessary re-evaluation of our field’s fragilities always seems destructive. As far as I’m concerned, of all the creative arts, visual arts is by far the most out of touch and elitist. Literature, cinema, dance, music, all seem either antiquated (opera) or potentially enjoyable to the average person who likes watching a show or picking up a book. Contemporary art exhibitions, however, are not a sure shot. When I’m not with my art peers and friends, if I’m asked what I do for a living, I’m invariably confronted with the comment that kills: “oh, I don’t know anything about contemporary art!”. And yet, we insist on shooting ourselves in the foot, but sadly, not with the post-noise swan song of the 1997 infamous Channel 4 show “Is Painting Dead?” chaired by Tim Marlowe who masterfully led a train wreck to its denouement with a dignity not many possess. Legend. (David Sylvester and Sir Norman Rosenthal made me cringe much more than a drunken Tracey Emin). Of course, what died was the willingness of the public to see artists and critics as anything better than pompous rich decadent people. Why do we put so much care and intention into the funeral of contemporary art? When we’re really, ultimately, burying ourselves? After all, Emin just closed her painting and bronze sculpture exhibition at White Cube gallery.

See the piece we cannot seem to shake away, Dean Kissick’s terribly written article for Harper’s Bazaar, “The Painted Protest”, whose subtitle is “How politics destroyed contemporary art” – a poor whodunnit, at least Tim Marlowe had us question if there was even a corpse. It starts with the unbelievable sentence “my mother lost both her legs on the way to the Barbican Art Gallery”. She intended to visit “Unravel", an exhibition about the political dynamics of textiles. According to the author, she inquired, still in hospital, if the exhibition was worth losing her legs for (she was almost writing his piece for him! As ever, mums do all the work!).

Forget about reading the ensuing description of the Barbican exhibition. I don’t know about you, but a thousand voices screeched in my mind about the mum, the legs, the tone, the hospital, the manipulatory narration. (In short story writing, it is advised to start with a striking sentence because the short story is, well, short. “The Painted Protest” start is so striking it leaves you with one of those light sensitive, nauseated migraines and a panic attack.) In short, Kissick claims that all art has given in to the politics of identity, and, therefore, museums are showing indigenous art, or art of the “past” (because we all know that indigenous people are the children of humanity). He seems obsessed with this idea of the now, and contemporary art as its most faithful guardian. But more importantly, he is nostalgic of the good old days of the beginning of the century when “Carsten Höller kept a herd of reindeer in Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof, fed half of them fly agaric mushrooms, and built a toadstool-shaped hotel room in which overnight guests could help themselves to the deer’s potentially hallucinogenic urine”. Ah, the good old days of animal exploitation and empty lyricism!

Everybody, with a few exceptions, tripped over themselves to claim that Kissick was a bit irrational but did indeed have a point. I must confess that this confounds me and scares me; it echoes an article I read recently stating that Bobby Kennedy Jr was crazy but he did speak the truth about [insert some obscure health fad]. Can we not find someone who includes the little speck of Bobby’s truth in a system that makes sense as a whole?

At this point I spotted that the David Zwirner Podcast had an episode about the inevitable backlash of “The Painted Protest”, where Helen Molesworth interviewed Kissick. I pressed play. She declared that they both seemed to get to the same conclusion but not through the same paths. The culprit is the discourse around art, she implied, and not art itself. So she tried to gear Kissick’s Nero-critique to exhibition texts. They could surely agree on that? In a motherly tone, she confided that when visiting exhibitions, she has “to make a huge effort not to blame the artist for the exhibition text”.

If the general attitude about contemporary art is claiming not to understand it, texts play a crucial role. They have to exist, and they have to provide some information. But what do they do, exactly? What kind of information should they convey? certainly not those big words people like me get enamoured with. That I learned. Or, yes, you can include them if they can disentangle a big knot and are crucial to understand the work. And you’re able to explain them.

But what are they there for? Storytelling? To inform? to explain the work? To contextualise it?

It’s about access. When a curator spends a lot of time in an artist’s studio and, more specifically, with their work, a strange things starts to happen. An osmotic relation establishes itself with a work that provokes a reconfiguration of perception, presence, outlook, choice, embodiment of values and opinions, curiosity, discovery. I have thought to myself so many times that I’m incredibly lucky to spend time with an artist’s process, and I wish more people got to do that. Therefore, it is part of my mission as a curator to facilitate this special type of knowledge, which is not academic, nor is it ingrained.

Giving access to this state is far more important than providing an array of facts about the artist or the exhibition concept. Of course, biographical details are important, as well as specific occurrences in the artist or the collective’s life. However, access is not given when you add platitudes to a short biography. That’s usually where politics, identity, social justice come in: how many “the artist questions [include a topic / a political injustice / a gender imbalance ]” have we read in introductory texts? When I read this, I envision the artist as a cartoon with a big question mark looking at some Big Problem. This is also how we tend to “sell” any content at the moment: it tackles “suicide”; it’s about “the role of women in society”. Soundbites, one-liners, easily packaged messages. This validates art because it becomes useful, serious, undeniably important rather than a mere indulgence in tones of blue.

Nevertheless, I believe in story, social awareness, formed specific identities and all the rest. I even think that they are the very basis of creativity. They’re not at the core, they’re not what we see, but they’re the shape of our eyes. Hiroshi Sugimoto’s trip to the beach, in the car, when he was a child, connected him to the sea in an inextricable way. It’s his story. Yes, because I do think that we can be a male - Japanese - ecological - oceanic identity. His art is not contained by it, it becomes independent from him, but it is built from that perspective. Landscapes form us, atmospheres, the male gaze, being beautiful, being neurodivergent, being traumatised, seeing flowers and smelling them. And I like stories, backgrounds, lived experiences. Art is not an object – it’s a dynamic entity, between object and mental image – it connects, it propels us to engage with ourselves and with others. Therefore everything around it should open it and not close it.

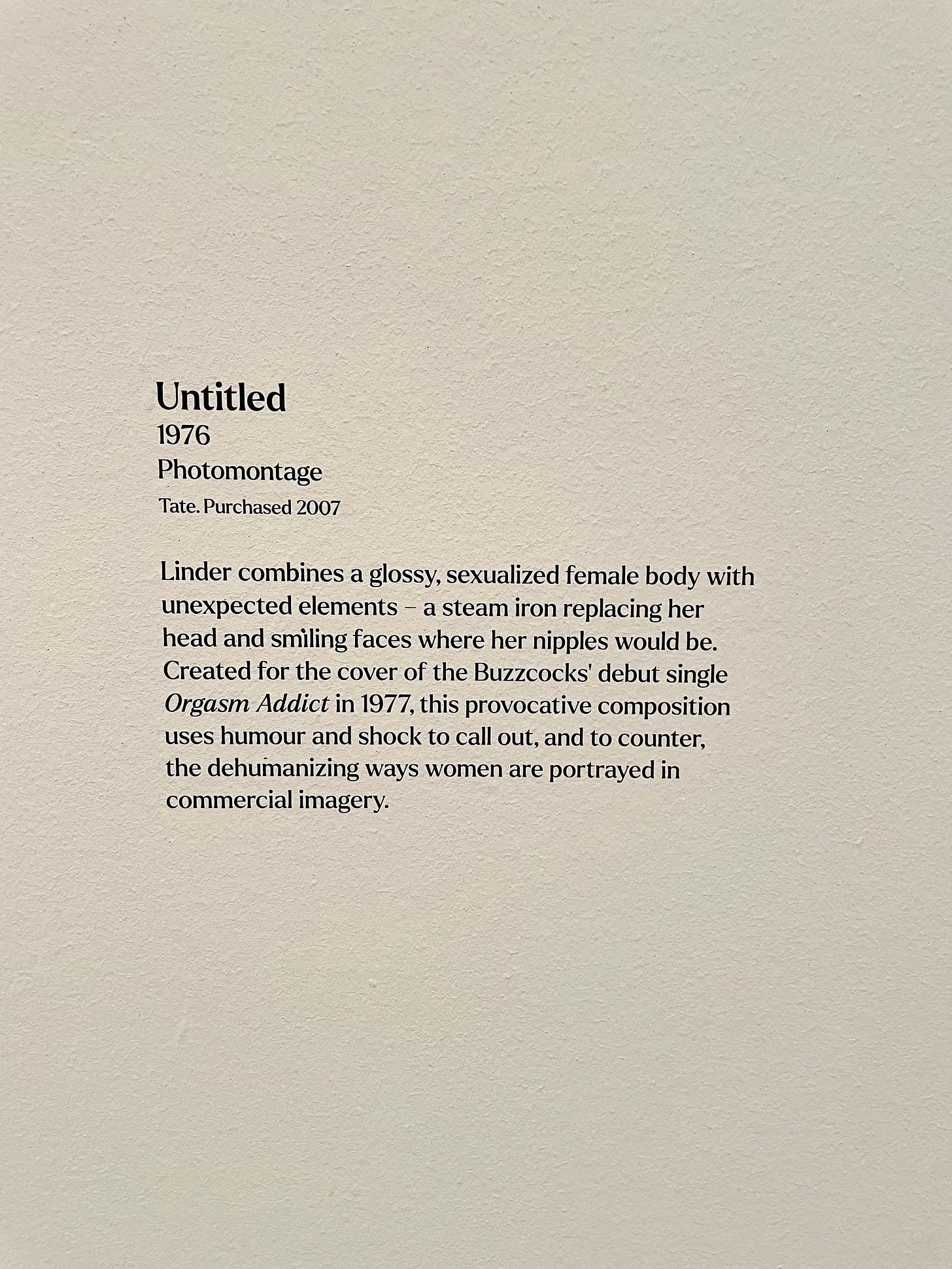

That’s why platitudes that solve the work for us [see the image], by situating it in some sort of Issue are terrifying and do not create long lasting connections with art and the artist. Suffice it to listen to Kissick and his apologists: we’re already sick of indigenous, non-white and female or trans artists. Some of us are just a trend to be forgotten. That’s why I want a text authored by someone in the museum who may want to give it a go, and interpret the work, provide a strange connection to it, have fun with it, engage with it. And I want it to be presented as such too – a person looking at the work and making connections. Even if the artist doesn’t agree (how artists are prescriptive with texts as well is a whole other annoying pet peeve of mine). So that the spectator knows that it’s ok to let go and fuck with the work as well, instead of trying to understand it. It takes years to shake off our understanding of art when we study it, and to really start eating it for breakfast.

Thanks for putting that out there. Couldn’t agree more.

Great article, Joana. I must admit that I'm very much an outsider to the contemporary art world/industry on the whole. (I'm learning!) My father, long retired, worked in graphic design and continues to paint, but otherwise I'm no different from any other visitor to the museum as far as the visual arts.

I studied music compositiion myself and there are some parallels perhaps shared by contemporary art and modern art music (as it has been called in the broadest sense). I guess my thoughts on this are similar to what I experienced as a student some twenty years ago, that the music I was studying was almost entirely sequestered and seperated from the world/community around it. As far as the community was concerned, it really served no purpose and, worse, did not try to; I never was sure if it was born of academic elitism or, just as likely, insecurity at opening up to wider public scrutiny. This resulted perhaps over time to one aspect in which the kind of music I was being exposed to seemed to continuously fail to consider, that our music should strive to say something about life, or how some purpose directed towards not just a particular (often highly-educated or wealthier) audience but to human beings as a whole. Or it could just be purposefully absurdist and silly (if that's not an oxymoron) for the sake of no meaning at all! (That has it's place, too.)

I joined a university trip to Ghana to study music, particularly of the Ewe, and one of the realizations in communities like that, where poverty was the unfortunate norm, is that music and art are essential aspects of life and perhaps even survival. It didn't have to explain itself, really, it was simply part of the fabric of daily life. In the West, where art and music have been so thoroughly commercialized as to have been rendered either innaccessible or meaningless, these artforms too rarely serve the purpose of pushing us forward or towards a more meaningful relationship with the world and the people around us. (Or are not given the opportunity to do so.)

I think my words are failing me, ha!, so forgive what may be rambling. While it helps to explain a work of art sometimes, other times it's best to bask in the mystery of it. Perhaps the curation and propogation of art is itself an artform--what needs to be said, what doesn't need to be said. As it is, I've already said waaaay too much. Thank you for you work!