Content warning: this text mentions sexual assault.

I went into Linder’s exhibition at the Hayward Gallery wondering about Punk. I emerged from it in a vertiginous loop of – seduction – danger – glamour – sex – cutting – and back again. The show threw me in a loop I usually prefer to avoid.

Born Linda Mulvey, the artist lived many lives, mostly within substantial cultural moments – starting with the Punk culture – albeit cultivating a sort of creative remoteness. The punks are now ‘pig farmers’, she told Ben Luke, explaining how being an artist is an ‘alibi’, a ‘catch-all’. Where she lives, if you say you’re an artist, you’re asked: ‘oils or watercolours? for an easy time, I sometimes say oils and sometimes say watercolours’.

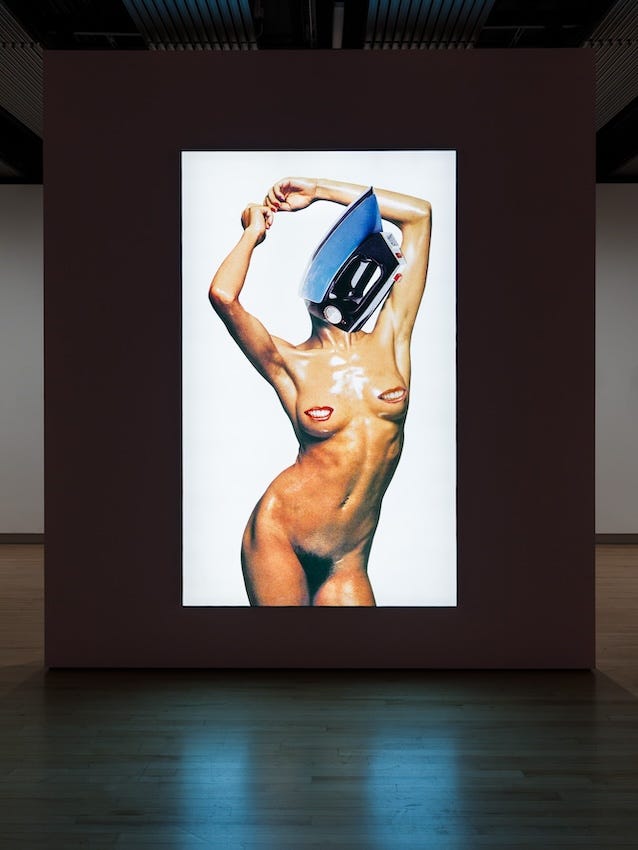

Linder is the person behind the famous photo-montage of a woman with toothy smiling mouths for nipples and an iron for head used as the cover for the Buzzcocks’ EP “Orgasm Addict” (1977). Discovering its original image tamed my apprehension of seeing the show. Such sibylline precision. I loved it. (I find a lot of photo-montage perfunctory and unimaginative). She was also in a band called Ludus; their second LP, “Danger Came Smiling” (1982) is the exhibition’s title.

Installation view of Linder - “Danger Came Smiling. It’s The Buzz, Cock!” (2015). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

In 1976, the artist went to a Sex Pistols concert in Manchester and fell in lust with the philosophy of punk, which she deemed dead as a movement in 1977 nevertheless. I say “lust” because when Linder describes becoming a feminist at 15 after she discovered Germaine Greer’s book “The Female Eunuch”, she seems to suggest not a break but a continuation of her unique blend of transgressive precociousness, linked in great part to a horrific part of her childhood.

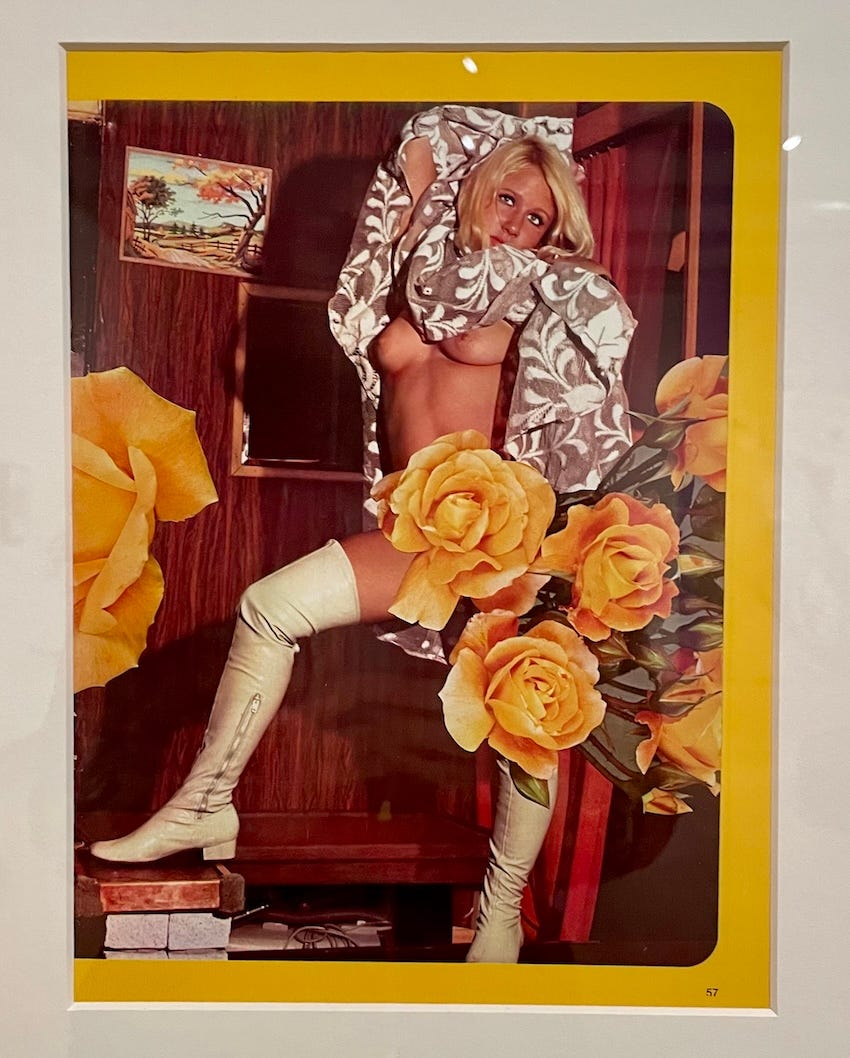

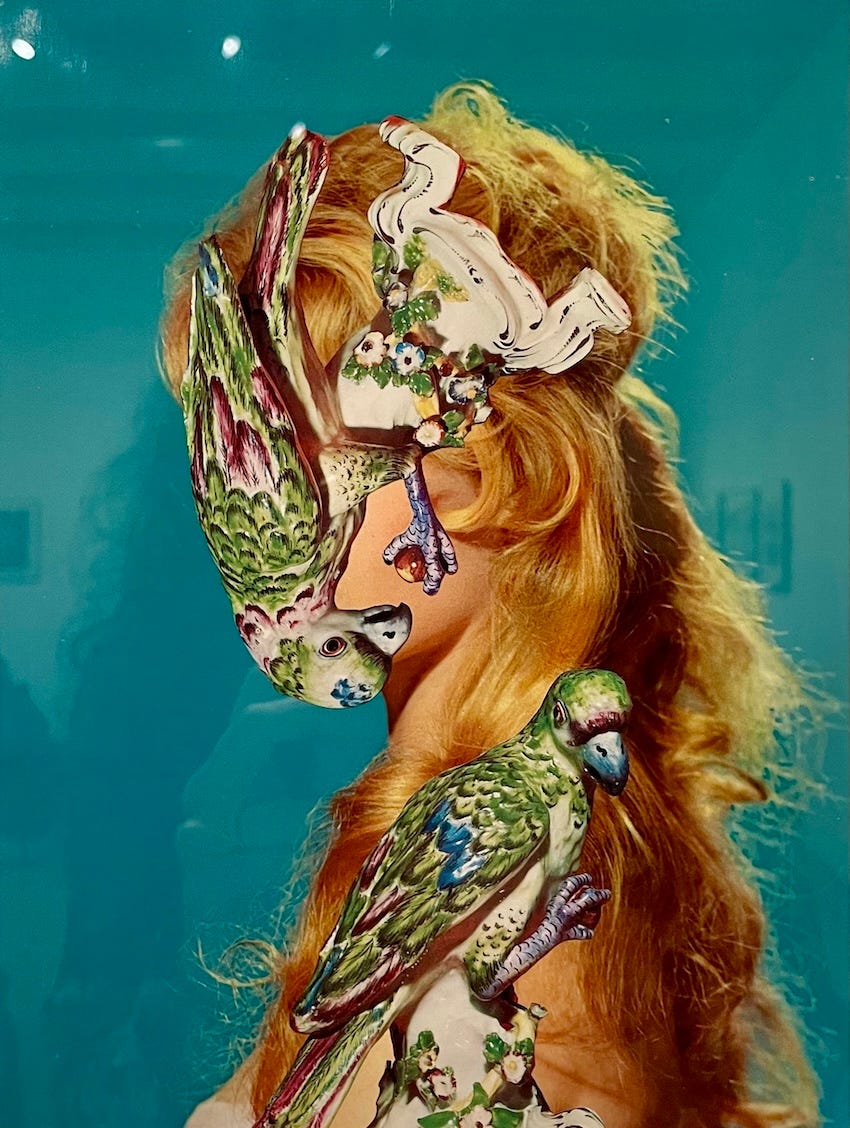

At a very early age, her psyche was tightly roped around aesthetic pursuits, women’s rights, female glamour, sexual assault, porn, cultural awareness, and pleasure. Linder, now 71 years old, accounts for her childhood with candour. She calmly explains that she was raped in the family home by her step-grandfather, after he’d groomed her with porn from age three (Linder was born in 1954). Recently, she underwent EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing) to conjure a new wave of intrusive images from that period of her life. But judging from the serene vividness of her interviews, this is not incompatible with collecting historic pornographic magazines. At times, she may even find herself in a bid for a rare item against renowned museums. However, if she obtains the vintage publication, she dissects it with her scalpel to extract material for her photo-montages, like a punk archeologist damaging the past and the future by weaving into the present.

In her childhood, the printed page was also the purveyor of ballet imagery with which she fell in love. In it, make-up and costume broke the barriers of gender, and the contorting bodies performed sinuous shapes with their own blend of transgression, a distorted echo of familiar pornographic choreographies. She also discovered Aubrey Beardsley, by mere chance, as her working class family wasn’t drawn to arts. He was another strange brew of precociousness, tragically deceased of tuberculosis at 25 in 1898, after having pleaded with a friend to destroy his “obscene” art. Fortunately, his beautiful line drawings where erotica flirts with ornament were preserved. Linder obsessed over his drawings, which she copied and elaborated from, with the only thing she’s ever stolen, a black Rotring pen.

Linder’s art for Ludus, a mix of Beardsley’s fine line black drawings, geometric post-punk and photo-montage. Photo: the author.

Lust doesn't die with assault; and Linder’s sophisticated mind didn’t avoid eroticism nor intellectual curiosity. Thus, Linder was drawn to “The Female Eunuch”’s cover (designed by John Holmes) and its philosophy. After all, she had already rejected the gender norming mores of her little town years before. If Germaine Greer is not a palatable feminist (she seems to pre-empt current ultra-capitalist feminism), she nevertheless urged women to investigate their own libido, affected by unchecked systematic submission, and analyse the system that killed it. That is, to explore sex and the self.

But does the loop ever stop looping to allow self-examination?

Indeed, John Holmes’ design is striking: it’s a bare female torso, with hyper-realist nipples, empty, like a corset made of skin, hanging on a rod by the shoulders; each side of the hips has a handle. In the later edition of the book, the same torso is drawn, simultaneously drowning in and emerging from a crimson background; it is white and covered with letters, the title of the book, written over and over like a punishment or an obsession; and the surname of the author, Greer, pops out proudly from the crotch of this hybrid creature. The alliteration of the author’s name is only visual. The letter ‘g’ is pronounced differently, a soft /dʒ/ and a guttural /ɡ/; and the two letters ‘e’ of the forename come together in the surname, pronounced /I:/, like a shout.

This cover reminds me even more of my looping mind after the exhibition (not less the title itself, interchanging male and female genitalia) racing from objectification – self-lust – beauty – sex – glamour – brains – rights – desire– and back again.

It’s one of those things. You challenge gender norms, empowering yourself by using your female attributes in your own terms, but then your released body becomes an image as arousing as the ones produced by the male gaze in its protuberant desire. You dismiss this. You don’t have to mother cis, straight males. Moreover, you desire your own body. But… is this desire perpetuated by the system you live in, claiming your undeniable beauty and unsurmountable seductive glamour?

Or it’s one of those other things. Objectification produces images suggesting liberation through sexual acts which play out gender releasing fantasies or free imaginations in a prop, texture, and toy delirium. It’s like child’s play. The pleasure membrane is stretched out.

In the third room, images of a “sploshing” session (below), a somewhat niche sexual fetish involving viscous, sticky foods spilled over the body, come at you as you enter. Linder organised this cathartic photo series when caring for her father, whom she had to spoon feed the type of foods used in this unusual sex rite.

View of the third room of the exhibition with images of Linder and a friend doing a « sploshing » session.

The show’s titillating title was taken from a novella belonging to Linder’s grandmother. Danger is not the same for boys and girls. The same liberating thing, image, or behaviour, can hurt you. Are we being manipulated by our own fantasies? Are they ours, really?

Buzzcocks EP cover 1977

I wonder about another title, “Orgasm Addict”, the Buzzcocks’ EP. The collaged woman remained a seductive body, whose unsettling features illustrated the male joys of over-masturbating. The point of view is masculine and the image is perceived as the sweet threat female beauty can be. It’s a funny song, celebrating the young person’s imagination: «You're makin' out with school kids / Winos and heads of state / You even made it with the lady / Who puts the little plastic bobbins on the Christmas cakes ». We’re not responsible for other people’s fantasies playing out in their minds. But who is?

It all started, for the onanistic young man, by « sneaking in the back door / with dirty magazines ». Their explicit images are taken from real life. The loop keeps looping: everything can be fuckable because the membrane of arousal covers the whole world in its absolute, yet timed, power. Linder’s photo-montages use porn imagery in interior, domestic spaces such as the kitchen or the living-room, or outdoors places where it would be difficult to walk around naked. Desire is a hallucination.

Linder was on another path altogether with her collection of porn from different decades of the past. She told the Guardian: “I think that kind of grooming [her own, as a child, with porn] begins with the handling of the child’s body in a certain way in domestic spaces. In my montages, I reverse-engineer what a paedophile spends their time engineering”.

« A Daughter’s Gift » (I forgot to write down its date). Photo: the author.

I guess that what I fear to ask is if reproducing exploitative images is reinforcing exploitation. Of course, Linder’s method is to forensically cut the imagery she was fed with a scalpel (literally, that’s the tool she uses) and release the women (and some men). She adorns and hides their genitals with blooms - nature’s porn, as she describes them - or shells. She details with evident care the time she spends with these women from the past, wondering if they could leave, why they were there and whether they were respected. She salvages the beauty of sex, of lust, of being overtaken by the soft violence of an orgasmic transe.

But the image above complicates this tale - unnervingly perpetuated by the wall texts in the exhibition - of the correction by scalpel. I believe that there is no correction. The cathartic release of re-framing, implies making a deal with the devil. It implies, to a certain extent, reinforcing. We know that behind the flower and in front of the model was a system of power. We also know that the people whose image we gaze at are the ones who are demonized rather than the machine behind them (as Mia Khalifa’s story proved recently). Porn is an industry with the almost mystical duty of weaving the oneiric fabric of our desires, which should be unleashed. But it’s made with real people, in real spaces, turned into forever images. Its influence lies subcutaneously, under tattoo inks and soft scarred tissue.

Incest, or assault bordering on incest, such as Linder suffered when she was a child, is not uncommon, it’s even trivialised and many times dismissed. Virginia Woolf’s claims of having been molested by her older brother were disregarded until recently, despite Woolf advocating for children in vulnerable contexts. Her mental health discredited her, instead of proving the assault. Ben Luke asked Linder, in more carefully crafted words, if the use of the pornographic image was a form of self-harm.

I cannot speak to that. I can only think of minor aggressions such the submission to beauty. Do women reject beauty despite it being a vehicle of objectification? Don’t we remain in the loop, looping it with our choice of seductive weapon, be it stilettos, lipstick, cleavage or mini-skirts?

Mabel Beardsley was rumoured to have had an incestual relationship with her brother Aubrey. This particular kind of incest transgresses the transgression through reciprocal love, which is reframed by childhood erotica – fairytales. Donkeyskin (Peau d’Âne) was asked by her father, the king, to marry him; he was obliquely obeying his dying wife’s wishes: to marry someone more beautiful than her. Beauty as the gateway drug to deviance. In response to Luke’s difficult question Linder muses: “in the process of grooming”, and she cuts away to say: “(…) interesting that (…) fairytales have so much to do with the groom, the bride and the groom, there is something already embedded in those stories – stories can warn (…)”. Abuse is tied with the idea of subjugating, youthful beauty, but masked by a dress, a prince, a castle, and a complex relation with male power.

Blinded by beauty, are women able to self-examine?

Linder, The Bardo of Dreams, 2024

In her lecture at the National Society for Women’s Service (21 January 1931), Virginia Woolf exercised her power of self-examination. She delivered a confessional speech whose agressive streak still astonishes me. The prompt was to talk about “professions for women”. Woolf spoke about her writing. She claimed that whenever she picked up the pen to review the work of a male writer the “Angel in the House” would intervene, urging her to diminish her qualities. She named this entity after a book-long poem by Coventry Patmore about the self-sacrificial role of women:

Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman's pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself.

(…)

And if he once, by shame oppress'd,

A comfortable word confers,

She leans and weeps against his breast,

And seems to think the sin was hers;

(…)

This is where the story takes a murderous tone. There was no other option, Woolf decided, than to kill the Angel in the House. This proved arduous, time-consuming. A time better spent “learning Greek grammar or roaming the world”. Irate, she even threw an ink pot at her. “It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality”.

But once the killing done, there should be no other presence in the room but the woman and her ink pot, Woolf posited: “in other words […] the woman had only to be herself. Ah, but what is “herself”? I mean, what is a woman? I assure you, I do not know. I do not believe that you know. I do not believe that anyone can know until she has expressed herself in all the arts and professions open to human skill”.

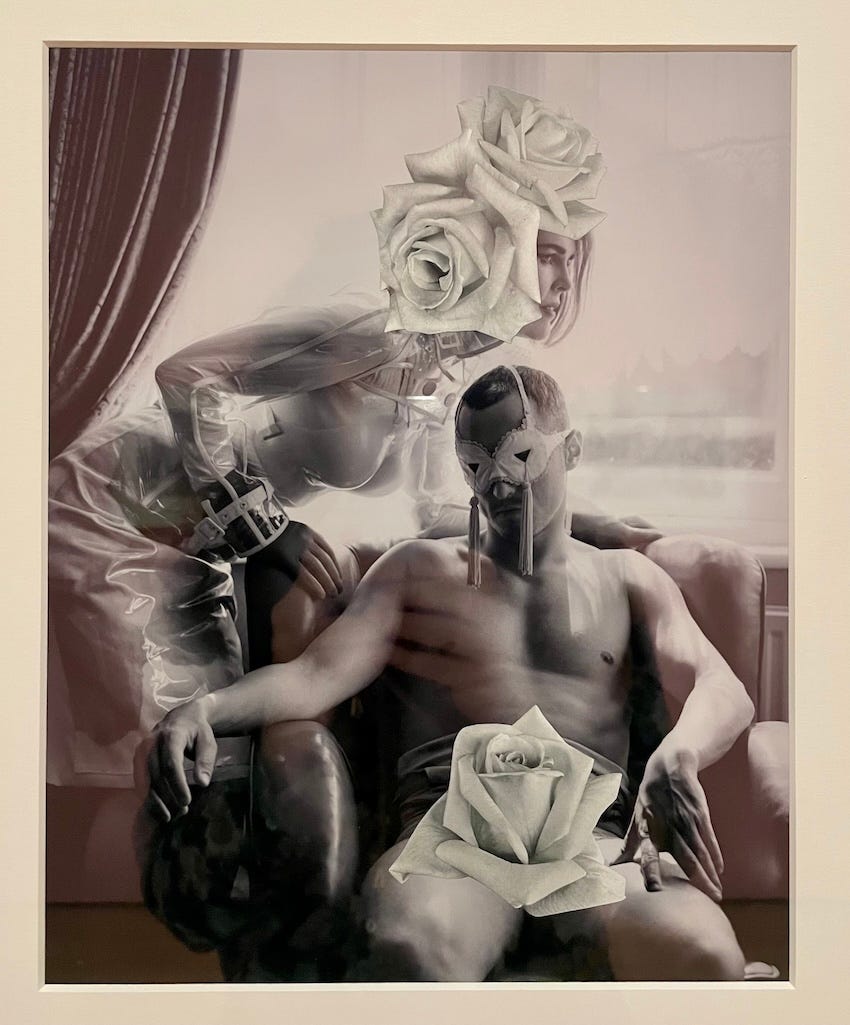

Untitled, Photomontage on photographic paper,2009 - Photography: Tim Walker

Let me tell you that Linder’s work mesmerised me. I see the image above as a cyborg angel (the face is Linder’s) convincing the contemporary male to queer his sexuality. There is a version of the tasseled mask he wears in the first room of the exhibition. “Danger Came Smiling” mostly spoke to memories of girlhood, not because of the dated origin of the cuts, but for their pre-pubescent feminine fascination with beautiful things, later sexualised. For the sexless sex, for the cultural epidermic desire to embrace womanhood in its drag form, when I was a girl, as a uniform I had to acquire in the future while being trained to adore it.

The first room shows Linder’s girlhood smashed by punk and eighties techno, with the tasseled bondage/S&M masks, the make-up, the Ludus album covers. It revealed the adult Linder, and the modern interstices where her sexed self expanded and contracted, suspicious of commodified culture. She has an alternative soul – a thing of the past, which is painfully rendered in her interview with Mia Khalifa. Alternative lives were identifiable through clothes, music, images. A sort of identity drag not quite available today; our space is virtual. Deepfakes prompted Linder to glue her own face on porn sources in recent photo-montages.

There is a video, projected onto a floating screen in the middle of the second room, where Linder is seen on stage (where she’d wear pieces of chicken and a black dildo). The second video shows her body-building, lifting heavy weights while wearing eighties gym accoutrements. Her determined profile is statuesque, as are her strong legs – another sort of drag, through body enhancement. The two videos are shown in a loop, looping the two Linders, cutting through the female fabric, such as the Bloomsbury group, or German trans and queer groups did in the 1920s before the war. History loops the loop too.

Linder, SheShe, 1981. Silver bromide photographs from original negative. Courtesy of the artist, Modern Art, London, Blum, Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York, Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Paris and dépendance, Brussels. Photo: birrer.

To be seen, or perceived, is an unavoidable condition. Charles S. Pierce, the inventor of semiotics, established a complex system of signs which includes human and non-human communication. Leaves rustling is an indexical sign, carrying with it the message it conveys to the bird, to the cat, to the human, who interprets it in their own birdly, catly and human ways – communication is always translation. The negotiation between image, comfort, power, time, identity, material, and meaning is the work of the artist. To perform it, Woolf claimed that she accomplished one of the two tasks for future women:

“(…) Killing the Angel in the House – I think I solved. She died. But the second, telling the truth about my experiences as a body, I do not think I solved. (…) Outwardly, what obstacles are there for a woman rather than for a man? Inwardly, I think, the case is very different (…). Indeed it will be a long time still, I think, before a woman can sit down to write a book without a phantom to be slain, a rock to be dashed against".

In 2025, there are far more phantoms haunting the whole gender spectrum, all kinds of communities (and individuals within them) in a loop of their own. I know I’ve flung my mobile phone at my own personal Jesus. But what am I?

Sources:

Guardian, interview by Alex Needham

A brush with… Podcast (The Art Newspaper) by Ben Luke:

Hayward Gallery video:

Finally found the kind of writing I was looking for on this app. Thank you, Joana, for sharing it here <3

This was such a great read, thank you for putting it out there. The way you described the loop really stuck with me. That back-and-forth between sex shaping the self, and the self then seeking out sex that fits what it already knows. It’s such a real thing, and you captured it with so much clarity and honesty. I love how you explore these ideas without trying to force them into tidy answers.