Going viral: if your exhibition is reposted by Snoop Dog, does it matter?

When the media and social media, with its trolls and its trends, has a peak at contemporary art online.

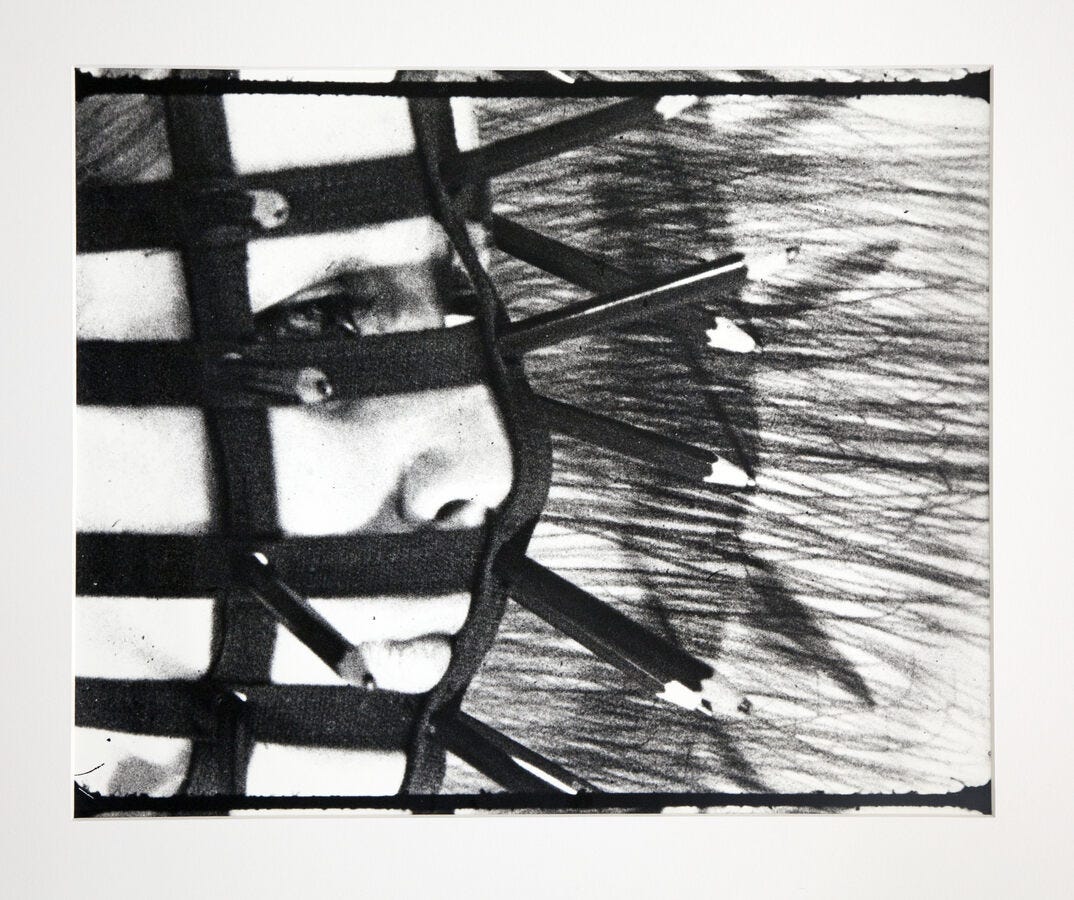

Saut n°8 (pour trampoline), performed drawing, 2022. Performed in en March 2022 at the Maison de la Culture d’Amiens for the exhibition HYPERDRAWING (Drawing Now Paris art fair 15th edition partnership with Frac Picardie).

«You’re a parasite», it said in my Instagram DM’s. In all honesty, I don’t fully remember what else was written because I compulsively deleted it. A stranger basically stated that people like me should be eradicated. By «people like me», you’ll be astonished to know, this person did not mean a woman, an immigrant, a neurodivergent person, or a vegan (yes, I’m all of those things). They meant a contemporary art curator. This was about a year ago. Until then, to my knowledge, one artist whose work I showed had trended for the wrong reasons, and another one reposted and mocked, but no one had been diligent enough to dig me up.

It’s fascinating how many thoughts can be thought in a split second. Before hitting “delete”, I remember marvelling about how sophisticated this troll was because they went for the curator behind the artist. They did their research. Here I am, substacking that independent curators are the unsung shadow workers of contemporary art, and now I was not only spotted but harassed for it. Can’t complain, right? In the Kardashiansphere being talked about is the goal, whether in good or bad terms. Clickbait is such an efficient tease that whether you rage-click or you love-click, the outcome is the same: audience numbers. Never has the adage “time is money” been so true. I just wish we were all more conscious of it (support independent content!!!). But I digress.

So, what does it mean for contemporary art to go viral?

Despite the vitriolic nature of my isolated DM, the artists with whom I collaborated, and who produce a certain kind of art which seems to poke bigotry more than others, were the real and constant target of vilifying reposts, which are still circumnavigating the internet. Performance art tickles people’s trolling fancy, and they go for it because – drumroll – we’re all millionaires. I hear you laughing from here, dear artists and colleagues. Especially if you think about the artists who were the target of these posts.

So let’s see. The first one was a young man, Emmanuel Béranger (who was then 25 years old). His performance piece Saut n.8 (pour Trampoline) was the first one to irate Tik-Tok overnight. Vertiginously, this is not hyperbole.

In 2021, Emmanuel Béranger had just graduated from ÉESI (Ecole Européenne Supérieure de l’Image), where the artist Marine Pagès taught drawing. She knew I was preparing an exhibition titled Hyperdrawing, after Timothy Morton’s notion of “hyperobject”, stating that everything we deal with in a globalised world menaced by the climate catastrophe will always have a scale much grander than the human one – everything is a hyperobject, of which we only have a partial experience, and inside which in fact, we live. There is no distance, there is not contemplation.

As a trace of an action, drawing equally seemed like a small part of a bigger phenomenon incorporating the spectator in the exhibition space. Therefore, Marine told me about her student’s work. Emmanuel Béranger’s performance pieces involve drawing because the movement of the body in space is marked with charcoal, or leaves traces on the wall. I hesitated at first, because he was so young, but I quickly told myself that if he produced framed drawings I wouldn’t think twice about it. So I invited him to participate in Hyperdrawing.

The event I was working on was a three-part exhibition for Drawing Now Paris art fair’s 15th edition in 2022 at the Frac Picardie, the Maison de la Culture d’Amiens (MCA) and the fair itself, at the Carreau du Temple in Paris. A considerable amount of exposure in our little milieu, but which was only a grain of sand buried under a layer of entertainment for the rest of the world. I was comfortable with my choice, especially because Emmanuel Béranger already had consistent work; I was able to put him in a position where he could be paid for it.

Performance artists will never see the work complete in their studios - the nature of their work unfolds in time and space before a crowd. Especially Emmanuel Béranger’s pieces which stem from his activity as a former competing athlete. His drawings are traces of jumps with precise moves; in competitions, if these are not observed, the athlete is disqualified. However, liberated from competition and judgement, the young artist focuses on the trace of the body’s movement. He performs the jumps 12 times according to their official protocol, but with a charcoal in his hand, which he drags on the wall throughout the jump.

The marks of his effort against gravity and toward observing the rules of the jump are thus left on the space, with the vibrating decisiveness of a physical effort performed by the whole body. It looks like a small drawing enhanced because there are hesitations - or, rather, places where he let go of the movement, unsatisfied, or where the hand had to stabilise the body. It could be a blown up line drawn on a paper, but a forensic study of it would reveal that, in spite of its apparent classical nature, the varying intensity and thickness of the line denotes a completely different engagement of the hand and the whole body, which traditionally, in European art, hasn’t been particularly relevant in drawing until recently. There is, indeed, a new strand of performative drawing since the 70s at least, which involves a holistic approach to mark-making: Rebecca Horn, Klaus Rinke, Helena Almeida, Morgan O’Hara, Carolee Schneeman, Trisha Brown, Mathew Barney…

Rebecca Horn / Performances II ‘Pencil Mask’ (‘Bleistiftmaske’) 1972, Film, 16mm )Film Still).

Sammlung Rebecca Horn © Rebecca Horn, Bildrecht Wien, 2021

I frankly thought that this kind of performance, which is a generous exposure and reinvention of the process of drawing, would appeal to general audiences (and perhaps therein lies the problem, “general audiences” is a concept performed by singular people).

Oh innocence. The MCA had just started a Tik-Tok account so I think Emmanuel’s performance was the second thing they posted. He performed in the evening of the exhibition opening where a whole crowd gathered. It was absolutely packed. Someone filmed it and posted it on the official MCA account. The morning after, we had about a quarter of a million views, the number seemed unreal. It was a hyperobject. The technological sublime.

We shrugged it off and kept working. What impact could it have on our little world anyway? To me, it felt like sending my kids to the shops and seeing them later in the background of a BBC News street reportage. And that’s when it started. The reel appeared on Instagram, on its own, or in compilations of "ridiculous” actions. There is (was?) something called “duets” on Tik-Tok, which is basically embedding one’s own post into another (in our case, the performance short video) and commenting it either with a snarky phrase or a little gif of the account owner making faces. Snoop Dog, or whoever manages his social media, reposted it.

However, the biggest surprise came with the ones stating that Emmanuel was making millions. This phenomenon could replace all the public engagement studies commissioned by art organisations to know how removed “general audiences” are from our small art village. Whereas Snoop Dog is worth 160 million $ (an estimation, of course but the real number and the estimated one cannot be that far apart), an artist can spend a whole year working on an exhibition and be paid for a solo show in France the minimum amount of 1200€ for the conception of the exhibition and 1200€ for copyright transfer according to DCA, the French association for the development of art centres, who specifies a “target” fee of 4800€. It’s hardly a fortune. I would bet my right leg that people posting these reels are a galaxy away from Snoop Dog’s yearly income. I’m aware that money is a difficult topic, and that everything is relative. What can I say, I still think if we payed more for what we consume and less for what consumes us, the world would be better off.

Anyway, we parted ways after the exhibition and I forgot about the reels. I imagined that Emmanuel’s experience was similar. Until I received the aforementioned DM and wondered how this viral phenomenon unfolded for him. What he wrote back was unexpectedly jarring:

“My relationship with this harassment (and the sudden visibility of my performances in general) has changed over time. At first, the discovery of the audience numbers creates a surprise and a kind of vertigo. Then the mass insults and unmitigated criticism in the comments created a second, even deeper dizziness that really got to me. (…) I was trying to respond, to argue why I was making these gestures and these works. The flow of comments was so enormous that it was useless, it was lost in the mass and sometimes led to violent insults. (…) I decided not to take this viral phenomenon into account in my approach to my work or to social networking. Today I continue to post my performances and my work on tik-tok and Instagram [my emphasis].

I block all insulting accounts and comments [my emphasis], not constructive criticism or questions. (…) Having received several private threatening messages (reported and blocked), I've been more vigilant about the presence of personal information on the internet (…) [my emphasis]. I often moderate my posts. Every time a new video is picked up by another account, it always looks a bit strange but it eventually goes away. I report them for copyright infringement but it never comes to anything [my emphasis].

Nowadays, I regularly come across people who have seen these videos and with whom the dialogue about art and sport opens up more easily. By meeting them, I tell myself that this visibility isn't all bad and that the vast majority of viewers are curious, even benevolent. In any case, it's a positive thing” [my emphasis].[Translated from French.]

There is a whole management of his social media account I was blissfully unaware of. Celebrities and female MP’s, for example, often complain about this; but most of them have a team which manages their accounts. Artists, on the other hand, live on a financial edge in an ultra-capitalist world where they do the work of a small company – the same goes for independent curators and small commercial galleries. (As I’ve overheard at a gallery dinner the other day, “no one is getting rich with contemporary art, bar a few exceptions”.)

I’ve come across another insulting video about the Bulgarian artist Boryana Petkova’s performance Link (2021) which I had also included in Hyperdrawing. I asked her how she reacted to it, and she told me that she considers this kind of harassment part of it – she’s used to trolling. She is aware of the fact that performance triggers people, which constitutes part of the attraction to the medium for her. I’ve always thought that she is in the Marina Abramović’ school of thought, at least the Abramović of Rhythm 0, (1974). In this performance piece Abramović was immobile for 6 hours next to a table full of objects that the viewers could use on her, and which ended with a man pointing a gun at her after several others had shoved things between her legs among other tasteless manipulations of her body. Petkova is tough as nails, and her work exposes and tests personal strength.

She sent me the post above which defends her performance, here reprogrammed at the Drawing Lab in Paris in 2024, starting with “this has been going viral for a few weeks now…”. Boryana seems to have chosen to envisage social media as a place of debate, rather than spiralling down the rabbit hole of hate, while being utterly conscious of and fuelled by it. As far as her finances go, it’s marvellous to note that at_brianhuntresss alludes to the trolls’ presumptions of her wealth by explaining the realities of performance art and its fees.

Marshall McLuhan’s famous statement “the medium is the message” keeps coming to mind. Whatever technology you use, be it a clay tablet and a stylus, a typewriter morphing into a book (a recent format…), or a screen where you tap and post immediately, your “message” is an amalgam of the content, the medium and the distributing platform. Instagram is a promotional vehicle of Image + Short Text. But it’s also a Tik-Tok adjacent, quick, witty, attention grabbing short moving image addled application (“reel or story”), appealing to low instincts. Not unlike “Rhythm 0” did, according to Abramović, who responded to it in “The Artist is Present” at the MoMa in 2010. But who is now selling wellness products too. The high/low aspirational pendulum swings, endlessly.

In September 2024, I interviewed the Canadian artist Carali McCall at the opening of her exhibition at Close Gallery in Somerset. During the opening, she performed Running Restraint, where she runs, extending an elastic strap hooked onto a wall behind her (or any other solid object, and even a person) and her waist, which pulls her back at each attempt, until she’s exhausted. Since its conception in 2010, she has performed this piece in Lisbon, Bexhill-on-Sea, several times in London, and recently at the opening of the 7th John Ruskin Prize exhibition, which granted her the Innovation Prize, at Trinity Buoy Wharf (January 2024).

RUNNING RESTRAINT (John Ruskin Prize) Live Performance, 6:30pm , Trinity Buoy Wharf, London UK

Interview for the opening of INFINITE: body, Landscape, Alchemy, and the Cosmos, solo exhibition, CLOSE Gallery, Somerset UK, 2024.

This time the artist received damaging comments in the post advertising the John Ruskin Prize iteration of Running Restraint on Instagram, which led to some disagreeable comments in the post of our interview. (Again, they did their research.) I noticed the latter, and made a mental note to reach out to her and explain that I’d seen this before, and how uneventful it was in the grand scheme of things. Time passed. I didn’t write. If I’m fully honest I felt a bit alarmist and ridiculous. At that point, I hadn’t contacted Emmanuel yet. Some time after, I received a message from her apologising for the comments and assuring me that the problem had been solved by closing the post’s comment section. I kicked myself again for not having reached out before and wrote back, explaining that she was not alone, I had also received a DM, it was not personal (only of course… it is, right?), and therefore it was inconsequential. That’s also when I contacted Emmanuel.

I’d just seen another reel of my performances orbiting the trolling galaxy and I’d started wondering if it was wise to dismiss it. However minimal, this was a trace of a global phenomenon – Hypertrolling. If Carali and Emmanuel weren’t traumatised, they weren’t unscathed either. Carali was unable to interact with her audience on Instagram, where so many work connections are made – and Boryana expected this to happen! The issue, for me, was the insidiousness of it, its imprecise outline, its affinity to abuse and harassment. So I asked Carali if she could send me a few thoughts about it. By then, I wanted to make sure I got its full dimension.

She wrote:

“(…) The reel that went viral was posted on Trinity Buoy Wharf’s public Instagram platform. It was a 20-second clip of the live performance-based artwork “Running Restraint” with text announcing the artwork winning the John Ruskin Innovation prize.

[It] was posted on the 28th of January. Two days after that morning I received a DM from the TBW who administrates the social media account, writing:

Hi Carali, hope you’re well! Just checking in- this video of you on our account went viral (4.4 million views at this point) and reached an opinionated corner of the internet. I’m worried you’re getting unpleasant DMs and annoying comments? Are you ok?

I then simultaneously had 6 or 7 DMs (male profiles) with comments such as ‘You are a r–––’, ‘Your artwork sucks’ etc. I deleted and blocked profiles immediately like it was a disease and contagious! I later started noticing on my other posts, and others’ posts, that I was affiliated with, public comments with ‘you are stupid’. The public comments on the original Reel on the TBW were such as ‘this is not art’, and ‘this is disrespecting athletes’.

I replied to TBW, saying:

Thanks for your message. And yes. That’s a lot of views. Not all are pleasant and some are very unpleasant/uncomfortable messages indeed. Quite the morning of reflection. A new experience for me. I really appreciate you checking in. If any suggestions. I’ll just keep quiet and let the wildness feeling fade. Appreciate you must be seeing this all too. best x

By the following day, the post had reached over 9M views and 21K comments.

TBW reply:

I wanted to add a couple of things: with this amount of views, it's inevitable to get random people saying things they wouldn't say in person. None of this is actually about you- just want to make sure you know that. Also, we didn't turn off comments, so they say their thing in one place and move on (otherwise they'll look for other places like your profile, or other non-related posts to comment under). This will run its course and fade away like you're saying, but keep in touch if it's not, and it's getting to you. x

We ended up ‘archiving’ the post for 3 days while things cooled. Immediately the DMs stopped. They ended up putting the post back up; untagged me, and with ‘comment” section “off”. So far that has been the end of it. Today it has 11M views. 11M views (total 4 weeks. 21K comments (2 days). 10 DM’s (2 days).

(…) It was the worry of whose opinions I do care about, and how this experience might affect or impact the work that weighed heavy on my mind. The first few DMs received, my feelings were – ugh, that hurts! Then, fuck, imagine receiving a note like this if you were a young girl, and your profile was “about you”… exposed to these attacks. I felt a fear of the ‘uncontrol’, and hurt by the ugliness and ‘love to hate’ human condition.

(…) when most of the profiles of senders of hate comments had ‘no images and a name with numbers – there is nothing to engage with. Messages like the one you sent me, acknowledging the fact I am not alone in this..And a friend at the time sent me the article on “Enshittification”.That was all helpful (…). It’s had some impact.

(…) I use Instagram as a ‘work place’, a profile page, brief introduction to my practice. (…). Performance art, like any creative expression, but perhaps the most vulnerable, invites different perspectives — some in admiration, others in critique, most in frustration – questioning what is it about. Therein lies the trouble, it’s all for interpretation and it is as personal as it can get when the artist uses their own body. (…)

To those engaging with the work, whether in support or scepticism, I ask what is restraint, and what forces hold one back. This experience tested that for me! [my emphasis].”

What strikes me is how difficult it is for all of us to clearly determine how and why this art trolling affects us.

A few weeks ago my husband asked our son B. to collect food we’d ordered from a restaurant, on his way back home from the tube. B. confused two shops. The forgotten shop called back, despite only a few minutes passing beyond the collecting time we’d provided; he accused us of “doing it on purpose”, as if he’d already decided that this was a plot against him. He refused to listen to my husband’s explanation, apology, and offer to pay for the food. B. went the shop to make amends on his way home; the person aggressively refused. That evening, my husband decided to leave a review of the shop on Google, detailing what had happened. The man called the following day, demanding him to take it down. When my husband said he’d do it if he listened to him – that’s all he wanted, naively thinking communication was possible – the man from the shop callously informed us that he had our son’s face in his CCTV footage. “In these streets, anything can happen”, he augured.

The threshold between virtual and real spaces of interaction is tricky. Performance turns reality into magic through a poetic physical action for those open to it; virtual spaces, for certain people, turn our physical bodies into unreal bags of flesh where any fear, contempt, or hurt can be projected.

Contemporary art will be fine. It’s the humans.

This is an amazing piece of writing. Thank you for sharing your experiences. It’s one of the best looks into the backstage part of the art world. This article humanizes the after effects of performance art or showing art at an event or posting art online. You touch on legal, psychological, and social aspects of art as a business and as a cultural reflection of this period in history. I was moved by the artists’ responses and also by your candid telling of how you handled these issues and your regrets and pride at different points along the way. I’m saving this one for reflection because I think there’s more to examine here psychologically and spiritually. Bravo.

What a chilling piece, Joana. It’s incredible, and deeply unsettling, how the internet, which was meant to connect us globally, has also become a space where people feel entitled to spread hate and bitterness, finding perverse satisfaction in tearing others down and leaving real impact on people’s lives. It hurt to read what your son experienced, what a sickening comment. To me this all comes down to the lack of basic art education. And beyond that: respect. Openness. A willingness to meet each other with warmth instead of cynicism. Thank you for writing this, it can’t have been easy, but it’s a vulnerable, powerful piece that will stay with me for a long time.