The Studio Visit At The Edge Of The Abyss

Studio visits, Alberto Caeiro & Fernando Pessoa. Visiting Irma Blank.

Studio visits are unlike any other socio-professional encounter. You penetrate a creative space where aesthetic singularity is overtaken by flashes of the mundane. You never know when artists delegate the process to the material’s own inventiveness, nor when they elevate what seems an inconsequential element. Sometimes, they seem fascinated by old or recent exhibition methods. Often, artists are entangled in a number of material conundrums which occupy the creative process far more than we’re taught in art history or curatorial studies, from demands of the market or the gallery to accessibility of materials and a certain idealisation of how they might behave. Others prefer to start from the material and obsessively talk about it in technical terms which they’d rather discuss with people who actually know them empirically. And finally, there’s the hybrid artist who captures the fluidity of life in its many facets through the stuff they use and the textures they’re drawn to in a sort of cosmology where the divine means dirt.

Many years ago, I was working with an artist who strings together what we’re taught to separate into basic needs and culture, such as, say, shelter and music. At the time, I naively saw their art as spiritual, and walked on egg-shells around them, trying to inquire about it in the right way. « And why this colour? How do you select your palette? », I asked. They gently laughed my question off by saying something like «Well, I don’t do a séance…».

I’m often reminded of Fernando Pessoa’s (1888–1935) heteronym Alberto Caeiro, my favorite, whose following verses have been tattooed in my mind since I read them more than thirty years ago:

“the only inner meaning of things

Is that they have no inner meaning at all”.

(V. Há metafisica bastante em não pensar em nada (There’s metaphysics enough in not thinking about anything. March 1914)

We study Pessoa in Portugal as such: Pessoa was many. He had a number of what is called heteronyms (and not a pseudonym, as one might think), “people” who wrote in and through him such as Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos, Alexander Search (the first heteronym, still in English, from his education in South Africa), and many others. He created their DOB’s and one of them even had a DOD (José Saramago wrote a book called The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1984)); they had astrological charts and full personalities.

The heteronyms knew each other; and the poet in whose internal theatre they gathered, Pessoa, referred to them as people - once, even, as as an alibi for tardiness to a date with Ofélia, the only woman with whom he had a relationship, albeit distant.

All of them considered Alberto Caeiro as the master. The Greek. The Pantheist. The heteronyms and Pessoa Himself - which is how Academia refers to him, or did, in my time - looked up to him.

The poem continues:

“(…) But if God is the trees and the flowers

And the hills and the moonlight and the sun,

Why do I call him God?

I call him flowers and trees and hills and sun and moonlight;

Because if, so that I might see him, he made himself

Sun and moonlight and flowers and trees and hills,

If he appears to me as trees and hills

And moonlight and sun and flowers,

It’s because he wants me to know him

As trees and hills and flowers and moonlight and sun.

And that’s why I obey him

(What more do I know of God than God knows of himself?),

I obey him, spontaneously,

Like someone opening his eyes and seeing,

And I call him moonlight and sun and flowers and trees and hills,

And I love him without thinking about him,

And I think him by seeing and hearing,

And I walk with him at all hours.”

For me, there were two moments in Caeiro’s logic.

Firstly, the acknowledgment that there is no inner meaning in anything. The rhetorical statement of there being a single inner meaning, which is that there is none, is a fallacy.

However, take some time with it, and you’ll stand before the abyss of those words: the absence of inner meaning is written with words which double, triple, quadruple what they stand for… they unfold the world to infinity. “Flowers” is repeated six times in the poem. Caeiro turns you against words as vehicles of duplicitous powers because they locate –they even create– beautiful lines in the universal shroud of the world which we must follow or flatten.

These verses terrified me.

5 December 2017, our first visit to Irma Blank (1934 - 2023).

When we saw the word BLANK between two surnames, next to a string of doorbells, we laughed. For us, these 5 letters carried such creative force that everything around it appeared trivial.

Was Irma’s surname a coincidence or linguistic fate? Since 1968, decade after decade, Irma had laboured on Eigenshriften in the 1960s–70s, then on Trascizioni in the late 1970s- calligraphies devoid of words but structured by text and, exceptionally, textile matrices; on linear brushstrokes the world called paintings, whereas she named them Radical Writings in the 1980s–90s, and whose deep blue columns of horizontal lines were led by her slowed down exhale and inhale; on texts juxtaposing several languages printed on reflective, steel modules or suspended polyester at the turn of the millennium; on a new alphabet with 8 consonants with which she created her Global Writings, and much more. Her materials were pastels, Indian ink, silkscreen printing, acrylic paint and Biro pens. Always between writing and drawing - perhaps reinventing a new form of reading. Her purpose was to free the word. To attain silence.

Irma Blank, Eigenschriften, 1969, ink on paper, 29,9x21 cm. Photo: C.Favero.

Irma Blank, Eigenschriften, 1968, pastel on paper, 21,6 x 15,6 cm Photo: C.Favero.

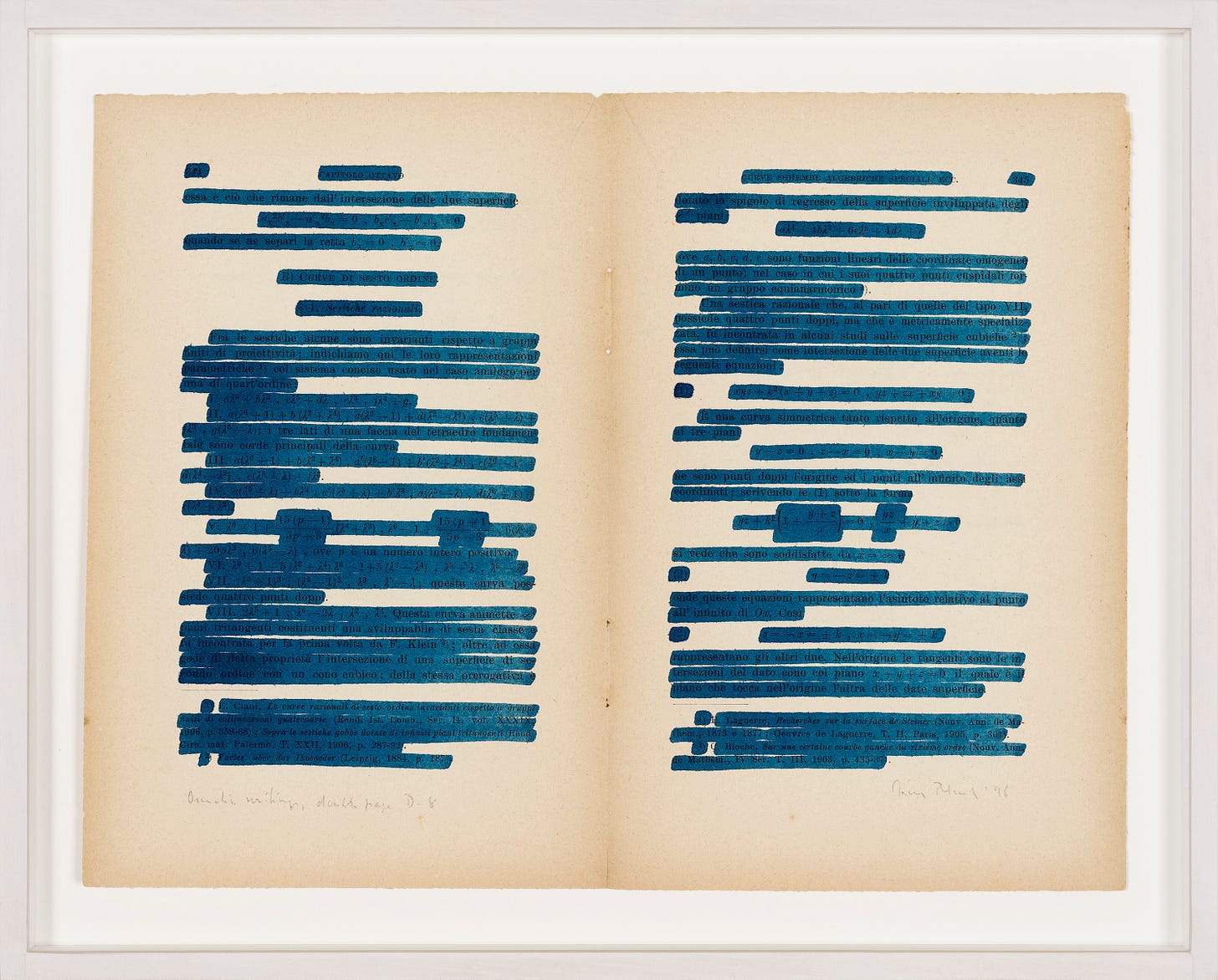

Irma Blank, Osmotic Drawings D-8, 1996, acrylic on paper, double page, 23,4x30,4cm Photo:C.Favero.

Irma Blank, Radical Writings, Abecedarium 9-3-91, 1991, oil on canvas, cm.203x75. Photo: C. Favero.

And there we were, before a door of a Milan flat, about to meet the person who created a work that had gripped us to the point where we decided, somewhat audaciously, to work on a touring exhibition proposal, titled BLANK (which came to happen, despite the pandemic). Johana Carrier, the co-curator of the project, a dedicated colleague and close friend, went in, as did I, following Alessandro Pasotti and Fabrizio Padovani, Irma’s two gallerists (P420 gallery). Inside, Irma awaited us, already, I think, with her daughter Rosanna whose wit and decisiveness was as rambunctious as it was crucial to the development of the project.

That first time we spoke with Irma is a blur because there were other subsequent visits and I didn’t keep a clearly dated account of our conversations. We probably focused on her biography. Born in Celle, Germany, in 1934, she settled in Italy in 1955 to build a life with a person she fell in love with, first in Sicily and then in Milan. An avid reader, she started reflecting on her experience between two cultures which led her to the abyss I had faced with Alberto Caeiro, and subsequently in my own life, lived, written and spoken in several languages, different tones of voice (French form inside the mouth and English inside the throat), different personas, different tendernesses, multiple unknowns in several languages or projected existences.

Her house had a studio at the end of a long, central corridor, where we would have intense conversations with her, mediated by the gallerists and the daughter because Johana doesn’t speak Italian and I understand it but cannot speak it well. That’s where she explained that after her diaristic series Eigenschriften, which means “writings for oneself” (the two first images), she tried, for the first time, to capture the shape of the world by reading books and newspapers with tracing paper over them, by re-writing the text in cohesive calligraphies without words –a type of drawing-writing called “asemic”.

Then we would move on to the kitchen, where we were served coffee and biscuits. I felt as if the irresistible scent of ground coffee beans lured me into passing the threshold onto worldliness and its half-translated chit-chat, but, more importantly, into the material condition of art and its spaces where the exceptional work of this octogenarian artist would find its place for a time. Curating is holding all those parameters together harmoniously while representing the work in an accessible and generous manner. So, that’s where we’d have animated conversations about the curatorial choices of each exhibition (until the lockdowns), which we chose to curate differently each time, due to the extension of Irma’s work. In pure Italian style, opinions were emphatically shared forming constellations of possibilities.

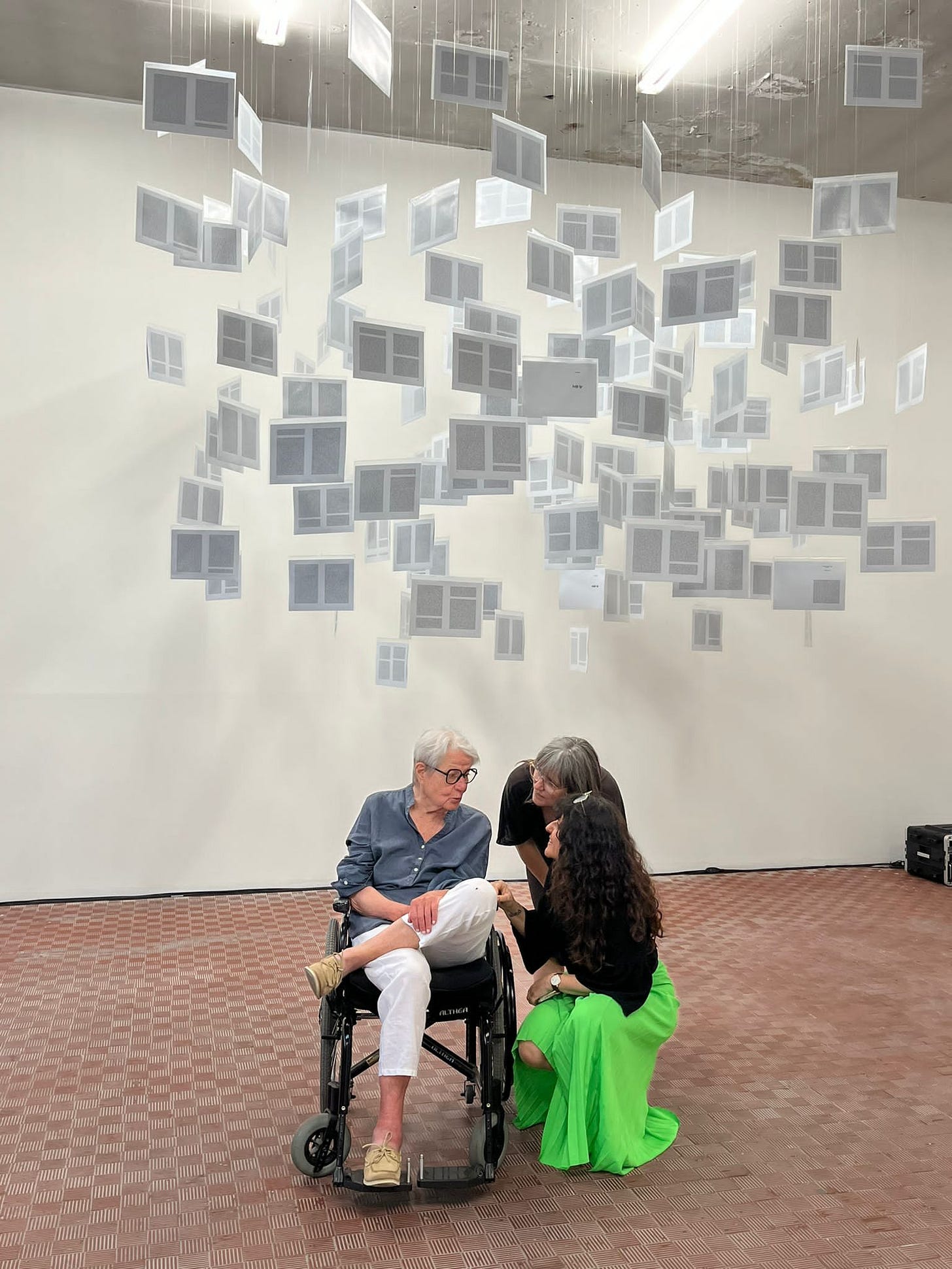

Irma Blank, Johana Carrier and me.

ICA Milano, the last iteration of our touring exhibition BLANK, from 09.06.2022 to 22.07.2022.

Little by little we gained Irma’s trust. She made sure we understood her focus, her entire project cut into series to which she would devote herself entirely before starting a new one. They reflected her inner states but also her view of the world through the word and the book. It was an oscillating focus between herself and the world as written word, which she would undo, like pulling on a woven thread, or tapping on a keyboard to overlap all the languages she knew, babylonically.

There were many books in the house, which she loved and read. With any other artist, I’d have asked to have a look and take pictures - I certainly had a glimpse, surreptitiously, but my abiding to her ethos of linguistic liberation obscures my memory. I only remember that her favoured literature was dense, philosophical and poetic.

After a few visits, I channeled some courage to ask: “but Irma, with your passionate reading, your love of language, how can you dismiss words?”. She was stern and funny - a strange combination. She replied solemnly:

“Well, you see, words are fossils”.

I said something like “ok, another incredible Blankian discovery to ponder over for a long time”, which made her smile. But I was serious.

I had that cavernous dread again. Irma often spoke of silence, and rejected references to Zen, Fluxus, or conceptualism, which she undoubtedly knew. But in the late sixties, nonetheless, when she was starting her first series in the idyllic but remote island of Sicily - and those philosophies in the Western artistic culture and movements were nascent -, she could very well have been in Antarctica. Back then, she was alone, with the hills, the flowers and the mountains, the flowers and the mountains and the hills.

That’s when, one day, she told us, while working in her usual spot in the kitchen, at night, when everyone was finally fed and sleeping, she noticed how the sound of the drawing echoed in the night, combined with the textures, and the repetitive motion. “I [became] very aware of sound—of my breath, of the scratching of my pen nib on paper”( Frieze in 2019). The roles were then subverted, there was no longer reception, there was emission; there was no conventional sign, there was a lifeline; there was no voiced information, there was breath; there was no separation between the world and the person, there was a person who was worlding; there was no need for explanation anymore because the folds were lifted and ironed out. There was finally the sparkle of communication.

She proceeded to record each sound of drawing, for each series, which we included in several iterations of BLANK.

But this is just the start. To know more about Blank’s meditative philosophy and her take on new technologies forming a global network, click play ⤵️

BLANK travelled to Culturgest, Lisboa; MAMCO, Genève; CAPC, Bordeaux; CCA Tel Aviv and the Bauhaus Foundation, Tel Aviv; ICA Milano; Museo Villa Dei Cedri, Bellinzona and Bombas Gens Centre d’Art, Valencia.

Start a conversation:

The quote from Caeiro--“the only inner meaning of things / Is that they have no inner meaning at all”.--reminds me of a Buddhist one: "Things are not what they appear to be / Nor are they otherwise."

I find it difficult to say precisely how these two ideas dovetail together, the difficulty of which may be one point of Irma Blank's work, but want to say that it is we, in our search for meaning, that impart meaning to things. Only human beings do this. Otherwise, their is no "meaning" as such in the universe apart from how we observe it, and through the observation, impart meaning (or none) to the things we observe. (This is a fundamental aspect of consciousness explored in Buddhism, such as symbolically represented in The Wheel of Yamantaka, though not in the sense of meaning per se.)

Breaking down language, we see that words are entirely constructed for the sake of impartiing meaning or communication, but on the other hand words are just shapes and lines (or sounds) which, devoid of an understanding of the language, become no more than that.

Standing before this particular void or abyss, I think one can see a kind of freedom in the inherent lack of meaning in things. We create it; it does not exist inherently, perhaps even in ourselves, and yet we still have been given (through divine grace? God only knows.) the capacity to create it. Nor do we have to take it all so seriously! (But we can too ... if we want to.)

The edge is a fascinating place to be, Joana. Terrifying, yes, but also wonderous. Thanks for sharing your experience!