Who Killed The Soul? (According to Tim Ingold)–Part I

A murder investigation in... a few Parts.

Ok, Maybe I’m being a bit facetious here but you get my drift. Tim Ingold is Emeritus Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen, Fellow of the British Academy and the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and an author we quote a lot in contemporary art philosophy and curating. For good reason. What he says resonates quite a bit with a lot of our preoccupations and fascinations. I must admit that when I started reading the text I quote below, I was taken aback. I have doom–fatigue, and I’m also conscious of the fact that a lot of leftie self-critique is echoed fascistically by the likes of Aleksandr Dugin whose crazy notions about the West start with the demonisation of our self-obsessed, narcissistic societies relying on individualism. There is nuance to embrace in all critique of what constitutes the values of liberalism because a lot can be said of selfless societies whose lives serve narcissistic and authoritarian leaders. But in great Tim Ingold fashion, complexity is embraced and there are no sweeping statements such as “egos are bad” or “indigenous philosophies are perfect”. Reality is, at best, murky when basic rights are seen as a narcissistic freedoms anyway so a profound exercise of judgement is paramount.

Full disclosure, I’m writing as I read Ingold’s text, so your guess is as good as mine. Who, indeed, attacked the soul? But first, let’s investigate its home and its friends and family.

Tim Ingold’s assessment of our data riddled epoch could be confused with diagnoses of peak decline, this nervous affliction of capitalism triggered by expectations of health as progress, history as inevitable growth. In his essay On not knowing and paying attention: How to walk in a possible world (2023)1, he wrote:

“Never in the history of the world (…) has such a wealth of knowledge, and such riches of information, been married to such poverty of wisdom”.

The lazy “there’s too much access to everything nowadays” is given the Ingold twist, by opposing knowledge and wisdom, as the difference in nature between the self and the soul. May the first have obliterated the latter?

The cornucopia of data we hold in our hands should produce a sophisticated human. It should excite curiosity; access to an endless string of facts, concepts, tales, numbers tied together with the bow of knowledge should facilitate education. Following the humanist ethos on which the education system shakily stands, this gift of access should enlighten the mind. But none of that happened, laments Ingold; instead, the flow of information at the reach of a finger on a keyboard outlines the subject. The I. The person, lulled by a powerful sense of self. How Ingold correlates knowledge and self resonates with a critique of the guiding principles of European culture.

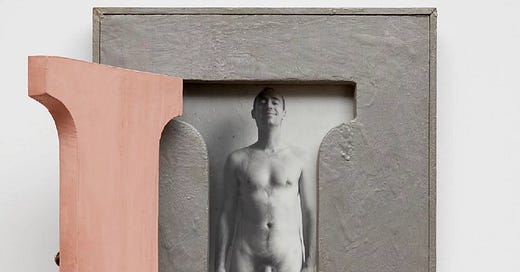

Robert Morris, I-Box, 1962, Painted plywood cabinet coated with Sculptmetal, photograph, 48 x 32 x 4 cm

What is the self?

The self is the isolated mind, the inquisitive and objective intelligence separated from the world. “The self is an invention of modern thought”, Ingold offers. With the nostalgia of the anthropologist, carried by the profound knowledge of how technologies (from the clay to the digital tablet) shape existences, Ingold’s views resonate with the need to decolonise art organisations and to evaluate the contemporary. He has been a cherished author in contemporary art circles since his book Lines, a Brief History (2007).

The present always confuses us, and, burdened with preoccupations around social justice, we’re baffled by technological invention : who would have thought that robots would finally exist as Intelligences while our own bodies became cyborgs ©️ by surgeons? What is this strange boundary of the self, if it’s not the body we were born with nor the brains trained by teachers to absorb data?

Modern thought can give us an answer. It has been doing it since 1641, when René Descartes published his Méditations Métaphysiques (its French title for a total of 6 “meditations”), birthing modern thought. There are other places of birth, certainly, this was not a single phenomenon but a continuous development. This text, however, is a small wonder which I will not belittle, even if it is, at times, rather comical. Descartes wrote a performative piece, a brazen philosophical experiment where the body of the philosopher is presented as the Guinea pig of theory. The astounding modernity of such a small text–my book is one of those school editions I’ve had for 32 years with more words dedicated to introductions and notes than the original text contains–cannot be overstated. It took me completely by surprise. Sitting in one of the classrooms of the Lycée Français Charles lePierre, I mindlessly heard Mr. Poingt, our philosophy teacher who looked like a cheerful Woody Allen, presenting it to us as a “proof of the existence of god”, en vogue in the seventeenth century. Unbaptised, agnostic by disinterest rather than conviction, allergic to history (at the time), I was unimpressed. Little did I know that I was to be gifted a 6-day performance of “what if everything I believed to be true wasn’t? I will proceed to play the game of doubting EVERYTHING”. To be clear: what impressed at the time was not the brilliance of such premise, but the childishness of it. How many late-night conversations such as these did teens have across generations, especially once we killed god as another philosopher would decry two centuries later, and his “Creation” became fair game? I was hooked.

But back to modern thought and radical doubt.

What was the first, and easiest object of doubt? The senses and the body: the first because they deceive the mind, and the latter because there is no basis of certainty emanating from a fleshy envelope which we can’t know for certain whether it is in a dream state or awake. Descartes was obsessed with “certainty”, with absolute basis of truth. So he excluded the senses because, of course, optical illusions. Then, he proceeded to probe the body as vehicle of truth: but how do I know whether I’m awake or asleep? I could be sleeping right now. I have dreams where I’m absolutely certain that I’m in a state of awareness. The body is the operative structure of the senses. It receives information through them, connected with imagination, a sort of playground of the senses associated with speculative but irrational faculties of the mind.

Delightfully, Descartes dismisses reality and his own body through the sheer power of speculation. Nonetheless, his own body is not only the testing ground of his experiments but also present in the text: described as naked in bed, or wearing a gown in his room warmed by a fire, where he is writing / performing theory. He’s like a conspirationist burning with fever, breathlessly claiming on instagram that Covid isn’t real. So while the philosopher discards empirical, embodied existence as a basis of truth, his body is present for the first time–that I know of–in a metaphysical text. And it is alone. The social or collegial angle didn’t occur to Descartes: community was not considered worth testing as a vehicle of certainty. The self was born in the fertile ground of individualism.

But there is more. What Descartes finds in the second meditation is not really what he tries to convince us of later, that is, the power of the principle of Reason: cogito ergo sum, I think therefore I am (which another teacher proposed to translate as je pense pour autant que je suis (I think inasmuch as I am). Thought is not present yet in his description. What he meticulously describes is how radical doubt produces awareness of a singular entity I identify with. Even if it is to say that I can’t know for sure whether what I believed so far to be reality really exists or not, the doubting mind is the only ever-present and reliable certainty thus far.

“But I see now that, without realizing it, I have ended up back where I wanted to be. For since I have now learned that bodies themselves are perceived not, strictly speaking, by the senses or by the imaginative faculty, but by the intellect alone, and that they are not perceived because they are touched or seen, but only because they are understood, I clearly realize [cognosco] that nothing can be perceived by me more easily or more clearly than my own mind.” (End of Second Meditation.)

Bodies are perceived by the mind, but only insofar as the mind deems them unreliable narrators of existence. Sheer existence arises through the annihilation of the world “out there”. The inner mind (we’d say our consciousness) is the only source of clarity. The self is alone, floating in a world of illusions and projections, rooted only through a critical, analytical and systematic operation, brought to you by the body of the philosopher, which may be naked, in bed, or “attired in a dressing gown, having this paper in [its] hands”.

By the third meditation, Descartes is clear about the state of things. There is an inner place where the self lives as the container of false informations and sensations, potentially. This resonates with Ingold’s description of the self as “an inner intelligence to which only I have immediate access”, turning us all into I’s. It is separate from the world “out there”, receiving and assessing information from the body.

(…) As I have already remarked, although the things I perceive or imagine outside myself do not perhaps exist, yet I am certain that the modes of thinking that I call sensations and imaginations, considered purely and simply as modes of thinking, do exist inside me. (Beginning of the Third Meditation.)

What are the consequences for the type of knowledge the self acquires? The self, explains Ingold, treats the world as its object (of study, of fear, of desire, of information) whereas the soul lives in it.

To be continued!

If you’re interested in my writing, and wondering if I take text commissions, I occasionally do. Get in touch below.

Tim Ingold, On not knowing and paying attention: How to walk in a possible world, Irish Journal of Sociology, 2023, Vol. 31(1) 20–36, © The Author 2022